Caravans and the Second World War

06/05/2020

As this country experiences one of the most testing periods in its history, it is fascinating to look back and see how people coped with adversity in the past. In May 2020 we mark 75 years since VE Day, and while the planned celebrations have been altered or put on hold for the time being, now is an opportune time to examine the role of caravans and caravanners during the dark days of the Second World War. While we are, of course, unable to travel at the moment, it is interesting to note that the can-do, all-in-it-together spirit of the community is as strong now as it was then...

During the 1930s, a growing number of families had access to a motor car, and enthusiasm for the trailer caravan holiday was growing at an incredible pace (along with Club membership numbers). However, the role of the caravan instantly changed in September 1939 with the onset of the Second World War, as fear of an imminent aerial attack by the enemy spread.

One and a half million of the most vulnerable, including children, expectant mothers and people with disabilities, were swiftly evacuated from cities to the safety of more rural locations. Owners of touring caravans quickly discovered that they were able to keep their families together by loading belongings into their cars, hitching up and towing to the safety of the countryside.

and a half million of the most vulnerable, including children, expectant mothers and people with disabilities, were swiftly evacuated from cities to the safety of more rural locations. Owners of touring caravans quickly discovered that they were able to keep their families together by loading belongings into their cars, hitching up and towing to the safety of the countryside.

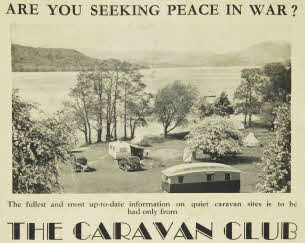

The introduction of petrol rationing limited the use of a caravan for leisure activities, and The Club took the decision to suspend rallies and social events for the duration of the war. Despite these factors, demand for touring caravans surged. Manufacturers, uncertain about the future, keenly advertised their stock as a way to stay safe in wartime. Caravan sites also opened up to evacuees, promoting themselves as safe havens for urban dwellers.

The Blitz

Despite widespread evacuation, bombing did not come as quickly as many feared and, emboldened by a feeling that the war would soon be over, many people returned to their homes by the end of the year. It wasn’t until the following September - 1940 - that the Blitz began in Britain, and air raids devastated the capital and other towns and cities. As more families found themselves homeless, there was a huge demand for touring caravans, but by this time many good-quality ’vans had already been snapped up. Some bomb victims were housed in quickly-built caravans of a poor standard at great concern to those who had worked hard to establish the good name of the trade.

A member of the Home Guard and a young recruit with evacuees and their trailer caravans at Elstree, 1940

A member of the Home Guard and a young recruit with evacuees and their trailer caravans at Elstree, 1940

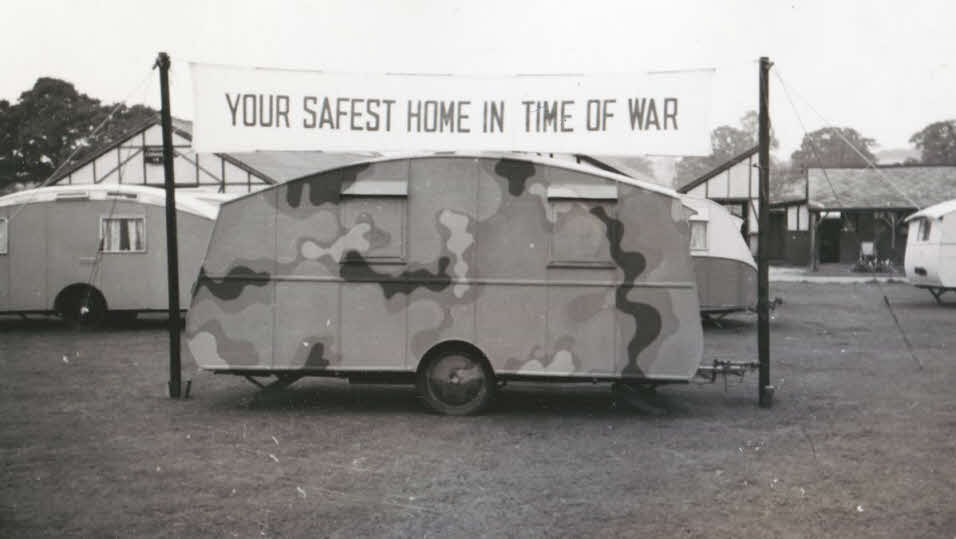

With very few holidays being taken, The Caravan Club found a role in supporting and providing advice to the influx of new caravanners making ’vans their homes due to evacuation and bombing. Club membership numbers continued to rise throughout the war, as the organisation advised even the most experienced on how best to prepare for a time of great danger. The Caravan magazine was awash with practical advice on how to make your outfit safe from the enemy, including how to black out windows to block out light and methods of camouflaging tourers with paint, netting and branches.

A camouflaged caravan advertised as the ‘Safest Home in Time of War’, 1940

A camouflaged caravan advertised as the ‘Safest Home in Time of War’, 1940

As winter neared, wartime caravan dwellers faced the challenge of preparing their poorly-insulated vehicles, originally designed for fair-weather holidays. Effective insulation had not been developed, so owners set to work modifying wall linings and installing stoves. These changes proved vital in order to reduce condensation, with many reporting that the damp could soak mattresses and bedding. The Caravan magazine’s editor, Bill Whiteman, even reported that he woke one morning to find his hair stuck to the wall by frozen condensation! Yet these wartime improvements contributed greatly to the development of better ’van insulation.

The Vicar of Upnor, Kent, and his wife lived in a caravan after struggling to get fuel for the vicarage, February 1943

The Vicar of Upnor, Kent, and his wife lived in a caravan after struggling to get fuel for the vicarage, February 1943

Despite the hard winters, caravanners reported that they found themselves in much better health. It was also claimed by one caravan dweller, Mrs Murray of Middlesex, that ’van life provided greater safety from direct bombing. She reported in The Caravan that after a near miss her outfit was sent flying into the air, and she herself was shot across the caravan and onto a mattress – but, astonishingly, not even a window was broken!

As the war came to an end in 1945, evacuated caravan dwellers gradually returned to their homes. Yet for those whose houses had been completely destroyed, caravan living was a more long-term prospect until large-scale home building projects took effect in the 1950s.

Post-war holidays

In the month following VE Day – June 1945 – Whiteman looked to the future in the pages of The Caravan: “The holiday demand will be a very eager one, and after six years of war, holidays are not a luxury but a real need for war-strained civilians, quite apart from for the servicemen to be discharged.” It was his feeling that “caravan holidays will be just what will appeal to thousands of civilians, pent up in factories and offices for long hours all these years, and to servicemen who have got used to the open air.”

By 1947 the Club membership number had risen to 4,000 and members gradually headed back to Europe on tours. As restrictions on petrol and materials were lifted, caravanning entered a golden age in a Britain that was determined to enjoy its freedom.

To find out more about the history of the Caravan and Motorhome Club, visit nationalmotormuseum.org.uk and follow @camccollection on Twitter.